The Noncommissioned Officer Candidate Course (NCOCC)

At the time of my initial 1999 research in to

the Skill Development Base Program in 1999

little had been written on the story of not only

this revolutionary new way to develop

sergeants for combat, but the men who were

chosen for training for that singular purpose.

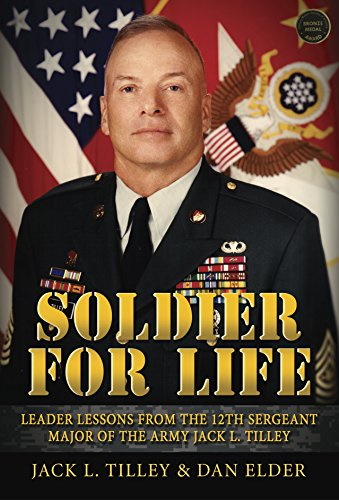

Since that time there were at least 3 books

written, including my monograph Educating

Noncommissioned Officers (of which this is

based on), yet the stories continue to be told.

Even among the attendees or the soldiers of

that period, little is known beyond anecdotes,

rumors or lore.

-CSM (Ret.) Dan Elder, Curator

Download the document here.

Prologue – Studying the Effects

of NCO Training

In 1957 the U.S. Continental Army Command

(CONARC) and the U.S. Army Leadership

Human Research Unit (with support from the

George Washington University) began to

study the feasibility of identifying and

training enlisted soldiers in the event of

hostilities to perform in leadership roles.

Long-recognized that the NCO was important

to the smooth operation of the Army, there

had been relatively little research conducted

on improving their training. Task NCO was

thus born, with the goal of determining how

to identify and train enlisted soldiers as

NCOs. Parallel research programs were

begun, with the Human Resources Research Office (HumRRO) of George Washington

University developing initial psychological

predictors of leadership potential and the

evaluation system for use in identifying

competent leaders for senior NCO positions.

The U.S. Army Personnel Research Office

(USAPRO) had the mission of developing

techniques to identify early in the careers of

those enlisted men who were capable of

becoming good noncommissioned officers in

the combat branches.

The Army Noncommissioned Officer’s

Academy system was selected to serve as the

framework to measure leadership

performance. The commander of the U.S.

Constabulary force in Europe Maj. Gen. Isaac

D. White decided late in 1949 that special

training was needed for the noncommissioned

officers of the Constabulary. He turned to the

commander of the 2nd Constabulary Brigade

Brig. Gen Bruce C. Clarke, who expressed his

enthusiasm about the project. White gave him

the mission of organizing a

Noncommissioned Officer Academy in

unused buildings at Jensen Barracks in

Munich, of which he was to also serve as the

Academy’s Commandant. White explained

what he wanted of the curriculum and stated

it would be run on a strict military basis. It

was to be purely academic classroom

instruction, not hands-on training. Clarke set

up a six weeks course with White’s approval,

and in September 1949 the Constabulary

Noncommissioned Officer Academy was

established. In later years, Clarke would

consider the NCO Academy to be one of the

most successful activities he had been

charged with in his illustrious career.

Initially, the HumRRO project was to study the effects of academy training on

noncommissioned officers job performance

and to study the factors that modify effects of

academy training. But at the urging of the

CONARC Human Research Advisory

Committee, HumRRO ultimately settled on a

three-phase study. According to CONARC

they believed that in a future mobilization that

“the need for enlisted leaders would far

exceed the number available from both the

active Army,” and that the need for NCOs so

pressing that they might be required to

“appoint leaders before their ability could

actually be proved on the battlefield.” One of

the early results of the study was the

publishing of the USCONARC Pamphlet

350-24, Guide for the Potential

Noncommissioned Officer, which was a howto guide for candidates to smooth the

transition for enlisted soldiers from within the

ranks to a sergeant.

In June 1961 Russia demanded the

withdrawal of western forces from the

German capital of Berlin and then started

constructing a wall to divide the city. In the

midst of those studies and field experiments

the Army and the Department of Defense was

faced with a possible call for mobilization as

a result of the Berlin Crisis. HumRRO

suggested that a two-week Leader Preparation

Course (LPC) between Basic and Advanced

training be instituted. The goals were to

provide support to the training cadre at

advanced training sites and centers, and

provide these leader trainees with supervisory

and human relations skills. In October, the

Leader Preparation Program (LPP) was

implemented at Forts Dix, Knox, Gordon,

Jackson, Carson, and Ord. In 1963 a oneweek Leader Orientation Course was provided to the Women’s Army Corps, to be

conducted one-week before basic training.

The LPP was based on a four- week LPC and

consisted of training programs and

observations. As to be expected for a program

of this type, there was resistance from the

“old soldiers.” The researchers noted that at

each training center they had to contact and

persuade approximately 30 officers and 100

NCOs to adjust their procedures, and to

convince them the system would work.

A series of pilot studies was conducted to

examine the problems of junior NCO

selection, prediction and evaluation of new

recruits. Informal leadership training was

conducted using different approaches and

techniques, and by the completion of the

study three experimental training systems

were developed. The 1967 conclusions drawn

up at the close of the10-year study were that:

Leadership Selection. The candidate

for leadership training should be above

average on BCT (basic training) Peer

Ratings and on the appropriate

Aptitude Area score. Supervisors’

evaluations should be used to eliminate

men who are obvious misfits or to

recommend men who are outstanding

prospects in the opinions of the cadre

despite poor aptitude scores or low

Peer Ratings.

Leadership Training. The

experimental training methods led to

better leadership indications on nearly

all criteria, with the Leader Preparation

Course system exhibiting greatest

effectiveness and feasibility among

various experimental and control

conditions tested.

Training Method. Relatively little

criterion difference was found between

results from specific training methods

(i.e., functional context versus

traditional; high cost versus low cost).

However, because the time involved in

presentation of each different method

varied, definitive comparisons could

not be made.

The CONARC-sponsored Unit NCO project

was directly influential on important changes

to the way the Army trained initial entry

soldiers. In 1963, Stephen Ailes, then

Secretary of the Army, made a

comprehensive survey of recruit training in

the Army. The Ailes Report recommended

establishment of schools that would offer

formal instruction to trainers newly assigned

to duty at Army Training Centers. The project

was organized at Fort Jackson during the

period 1 February-17 April 1964. CONARC

developed a new concept to transfer

responsibility from training committees to the

platoon sergeant. Technical advisory in the

development of the “Drill Sergeant” was

provided by the Work Unit and the LPP

served as the model for the Drill Sergeant

Program and in developing the Drill Sergeant

Course, first conducted at Fort Jackson.

The Noncommissioned Officer’s

Candidate Course

As the war in Vietnam had progressed, the attrition of combat, the 12-month tour limit in

Vietnam, separations of senior

noncommissioned officers and the 25-month

stateside stabilization policy began to take its

toll on the ranks of enlisted leaders to the

point of crisis. Without a call up of the

reserve forces, Vietnam became the Regular

Army’s war, fought by junior leaders. The

Army was faced with sending career noncoms

back into action sooner or filling the ranks

with the most senior PFC or specialist. Field

commanders were challenged with

understaffed vacancies at base camps, filling

various key leadership positions, and

providing for replacements. Older and more

experienced NCOs, some World War II

veterans, were strained by the physical

requirements of the methods of jungle

fighting. The Army was quickly running out

of noncommissioned officers in the combat

specialties.

In order to meet these unprecedented

requirements for NCO leaders the Army

developed a solution called Skilled

Development Base (SDB) Program on the

proven Officer Candidate Course where an

enlisted man could attend basic and advanced

training, and if recommended or applied for,

filled out an application and attended OCS.

The thought by some was that the same could

be done for noncoms. If a carefully selected

soldier can be given 23 weeks of intensive

training that would qualify him to lead a

platoon, then others can be trained to lead

squads and fire teams in the same amount of

time. From this seed the Noncommissioned

Officers Candidate Course (NCOC) was born.

Potential candidates were selected from

groups of initial entry soldiers who had a

security clearance of confidential, an infantry score of 100 or over and demonstrated

leadership potential. Based on

recommendations, the unit commander would

select potential NCOs, but all were not

volunteers. Those selected to attend NCOC

were immediately made corporals and later

promoted to sergeant upon graduation from

phase one. The select few who graduated with

honors would be promoted to staff sergeant.

The outstanding graduate of the first class,

Staff Sgt. Melvin C. Leverick, recalled “I

think that those who graduated [from the

NCOC] were much better prepared for some

of the problems that would arise in Vietnam.”

The NCO candidate course was designed to

maximize the two-year tour of the enlisted

draftee. The Army Chief of Staff Gen. Harold

K. Johnson approved the concept on June 22,

1967, and on September 5 the first course at

Fort Benning, GA began with Sgt. Maj. Don

Wright serving as the first NCOC

Commandant. By combining the amount of

time it took to attend basic and advanced

training, including leave and travel time, and

then add a 12-month tour in Vietnam, the

developers settled on a 21-22 week course.

NCOC was divided into two phases. Phase I

was 12 weeks of intensive, hands-on training,

broken down into three basic phases. For the

Infantry noncom, the course included tasks

such as physical training, hand-to-hand

combat, weapons, first aid, map reading,

communications, and indirect fire. Vietnam

veterans or Rangers taught many of the

classes, but the cadre of the first course was

commissioned officers. The second basic

phase focused on instruction of fire team,

squad and platoon tactics. Though over 300

hours of instruction was given, 80-percent

was conducted in the field. The final basic phase was a “dress rehearsal for Vietnam,” a

full week of patrols, ambush, defensive

perimeters, and navigation. Twice daily the

Vietnam-schooled Rangers critiqued the

candidates and all training was conducted

tactically.

Throughout the 12-weeks of training,

leadership was instilled in all that the students

would do. A student chain of command was

set up and “Tactical NCOs” supervised the

daily performance of the candidates. By the

time the students successfully completed

Phase I, they were promoted to sergeant or

staff sergeant, and shipped off to conduct a 9-

10 week practical application of their

leadership skills by serving as assistant

leaders in a training center or unit. This gave

the candidate the opportunity to gain more

confidence in leading soldiers. As with many

programs of its time, NCOC was originally

developed to meet the needs of the combat

arms. With the success of the course, it was

extended to other career fields, and the

program became known as the Skill

Development Base Program. The Armored

School began NCOC on December 5, 1967.

Some schools later offered a correspondence

“preparatory course” for those who

anticipated attending NCOC or had not

benefited from such formal military

schooling.

As with the Leadership Preparation Course

tested by HumRRO, the “regular” noncoms

and soldiers had much resentment for the

NCOC graduates, as those who took 4-6 years

to earn their stripes the hard way, were

immediately angered. Old-time sergeants

began to use terms like “Shake ‘n’ Bake,”

Instant NCO,” or “Whip-n-Chills” to identify this new type on noncom. Many complained

by voice or in writing that it took years to

build a noncommissioned officer and that the

program was wrong. Many feared it would

affect their promotion opportunities, and one

senior NCO worried that “nobody had shown

them [NCOC graduates] how to keep floor

buffers operational in garrison.” William O.

Wooldridge, serving as the recently

established position of Sergeant Major of the

Army stated that, “promotions given to men

who complete the course will not directly

affect the promotion possibilities of other

deserving soldiers in Vietnam or other parts

of the world.” In his speech to the first

graduating class Wooldridge said that, “Great

things are expected from you. Besides being

the first class, you are also the first group who

has ever been trained this way. It has been a

whole new idea in training.” As Wooldridge

expressed, all were not suspicious of this new

way to train NCOs. After initial skepticism,

outgoing battalion commander of 2d Bn, 27th

Infantry Lt. Col. Winfried. G. Skelton was

asked how he though NCO Candidate Course

graduates performed in combat, to which he

replied, “within a short time they [NCOC

graduates] proved themselves completely and

we were crying for more. Because of their

training, they repeatedly surpassed the soldier

who had risen from the ranks in combat and

provided the quality of leadership at the squad

and platoon level which is essential in the

type of fighting we are doing.”

The graduates recognized the value of their

training. Young draftees attending initial

training at the time knew they were destined

for Vietnam. Many potential candidates were

eligible for Officer Candidate School, but

rejected it because they would incur an additional service obligation. They realized

that NCOC was a method by which they

could expand on their military training before

entering the war. Some were exposed to the

Phase II NCO Candidates serving as TAC

NCOs during their initial training and felt

they could do the same. Many graduates

would later say that the NCO Candidate

Course, taught by Vietnam veterans who

experienced the war first hand, was what kept

them and their soldiers alive and its lessons

would go on to serve them well later in life.

Many were assigned as assistant fire team

leaders upon arrival in Vietnam and then

rapidly advanced to squad or platoon

sergeants. Most would not see their fellow

classmates again, and in many cases were the

senior (or only) NCO in the platoon. Some

would go on to make a career of the military

or later attend OCS, and four were Medal of

Honor winners. In the end over 26,000

soldiers were graduates of one of the NCO

Candidate Courses.

The NCOC graduate had a specific role in the

Army-they were trained to do one thing in

one branch in one place in the world, and that

was to be a fire team leader in Vietnam. It

was recognized that they were not taught how

to teach drill and ceremonies, inspect a

barracks, or how to conduct police call. Many

rated the program by how the graduates

performed in garrison, for which they had

little skill. But their performance in the rice

paddies and jungles as combat leaders was

where they took their final tests, of which

many receiving the ultimate failing grade. But

educating NCOs and potential NCOs was

firmly in place for the Army.

Epilouge

The call was out in the Army to educate

noncommissioned officers. In 1963 a council

of senior NCOs at Fort Dix called for a senior

NCO college, and one of the main topics was

NCO education in November 1966 during

SMA Wooldridge’s first Command Sergeants

Major Conference. The Army began to look

at educating noncoms in earnest. On August

17, 1965, the Chief of Staff of the Army

directed a comprehensive Enlisted Grade

Structure Study. This study, which was

completed in July 1967, focused on how to

establish and manage a quality-based enlisted

force, and dedicated a portion for “improving

the vital area of training.” In response, the

Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel

developed a comprehensive 5-year plan to

manage career enlisted soldiers which

included many far reaching programs, such as

career management fields, MOS

reclassification, the Qualitative Management

Program, and Force Renewal through NCO

Educational Development.

The Project recommended formal leadership

training designed to prepare selected careerenlisted personnel for progressive levels of

duty, and noted it would enhance career

attractiveness and the quality of the

noncommissioned officer. This study

recognized that “The present haphazard

system of career development, as opposed to

skill development, had two bad results. First, the image of the NCO as a professional,

highly trained individual is difficult to foster;

second, the Army’s resource of intelligent

enlisted men, anxious to develop as career

soldiers, is inefficiently managed. The Army

has extended great effort to ensure the

selected development of its officers.

Analagous [sic] effort should be spent in the

development of the noncommissioned

officers of the Army.”

The report went on to recommend a threelevel educational program, similar to officers,

outlined in the February 1969 NCO

Educational Development Concept. The first

of the three levels consisted of the Basic

Course which was designated to produce the

basic E-5 NCO. The Advanced Course was

targeted to mid-grade NCOs, and the Senior

Course was envisioned as a management

course directed to qualifying men for senior

enlisted staff positions. The Skill

Development Base Program, NCOC, was

selected to serve as the model for the Basic

Course. Project Proficiency, to be now known

as the NCO Education System (NCOES), was

to become a reality.

On the 23rd of April 1970, President Richard

Nixon announced to Congress that a new

national objective would be set to establish an

all-volunteer force and from that the Modern

Volunteer Army was born. But by mid-1971

Army Chief of Staff General William

Westmoreland was unhappy with the progress

of the MVA and asked then retired Bruce

Clarke to travel the Army and find out what

could be changed to make it more attractive.

On a visit to Fort Hood, Clarke arrived in

time for its NCO Academy to close its doors,

a repeat of the same story at other installations. Clarke conducted a survey and

discovered that there were only four NCO

Academies remaining in which to train

100,000 noncommissioned officers. In his

report back to Westmoreland, Clarke

lamented that “we are running an army with

95% of the NCO’s untrained!” NCO

academies across the nation were reopened,

and Westmoreland approved the Basic and

Advance noncommissioned officer courses,

and by July the first Basic course pilot began.

Some of the difficulties facing the Army of

1971 included Westmoreland’s concern for

leadership inadequacies. He directed the

CONARC Commander to form a study on

leadership, and noted “the evident need for

immediate attention by the chain of command

to improving our leadership techniques to

meet the Army’s current challenges.” He also

directed the War College in Carlisle,

Pennsylvania to determine the type of

leadership that would be appropriate as the

Army approached the end of the draft. While

these studies were going on, the Army was

continually under fire. The May 1971 release

of Comptroller General’s Report to Congress

on the Improper Use of Enlisted Personnel

noted that the Secretary of the Army should

strengthen existing policies rather than

introduce new programs or changes. That

same month Westmoreland urged all the

commanders of the major commands to grant

their noncommissioned officers broader

authority. In his list of 14 points he asked

them to “expand NCOs education through

wise counseling and by affording them the

opportunity to attend NCO Academies, NCO

refresher courses, and off-duty educational

programs.”

NCOC seeds Army NCO

Education System

Planning for the development of an education

system for enlisted leaders of the Modern

Volunteer Army began in early 1969.

Obviously, if the NCO could be schooltrained for the jungle, then they ought to be

school-trained for the garrison, too.

Westmoreland had intended to establish a

senior NCO school in 1968, but CONARC

commander Gen. James K. Woolnough was

not enthusiastic about the plan. Woolnough

believed that senior NCOs, like generals,

needed no further military schooling. This

was the same problem Gen. Johnson was

earlier faced with while trying to establish the

NCO Candidate Course when CONARC

commander Gen. Paul A. Freeman and his

headquarters would not accept the idea.

Johnson opted to wait until Woolnough

assumed command of CONARC to begin the

NCO candidate program. Westmoreland

would also wait until Gen. Ralph E. Haines

Jr. succeeded Woolnough at CONARC for

the senior NCO school.

In July of 1970, during a lull in the NCO

Candidate classes at Fort Sill, they conducted

the first pilot of the Noncommissioned

Officer Basic Course. The NCO Education

Program could only begin when NCOC

Candidate Courses were completed because

of scarce resources…and the first of the

Army-wide courses began in May 1971. In January of 1972 the first two

Noncommissioned Officer Advance Courses

began and that same year Chief of Staff Gen.

Creighton Abrams approved the

establishment of the Senior NCO Course, to

be located at the newly established Sergeants

Major Academy at an unused airfield in El

Paso, Texas. The draft ended on December

31, 1972 and the Army entered 1973 prepared

to rely on volunteers.

The three-tiered noncommissioned officer

education system was initially developed for

career soldiers, specifically for those who had

re-enlisted at least once. Students would

attend the courses in a temporary duty status,

with the sergeants major course being a

permanent change of station. NCOES was

established in late 1971 and phased in across

the Army. Funding was a problem,

particularly with overseas soldiers and by

December 1971 CONARC had to cancel 9 of

12 Basic Course classes because of poor

attendance. CONARC convened a NCOES

conference in October and implemented

incentives including promoting the top

graduates, offering promotion points to

graduates and mandatory quotas by

CONARC. Reserve soldiers were authorized

to attend active courses, and different

branches developed correspondence courses.

In January 1972 the first two advance courses

started, consisting only of E-7s because the

Department of the Army did not maintain the

files of E-6s to screen. By 1974, forty-two

courses had been established through

CONARC, and in August U.S. Army Europe

personnel were allowed to attend advance

courses in the United States.

Dedicated to:

- SSG Robert J. Pruden, Class 2-69

- SSG Hammett Lee Bowen, Jr., Class 4-69

- SSG Robert C. Murray, Class 38-69

- SGT Lester R. Stone, Jr. Class 37-68

One Response

I am the photo editor for Vietnam magazine and I’m very interested in images to help illustrate a feature about the Shake and Bake program. Please contact me as soon as is possible.

Thank You

Guy